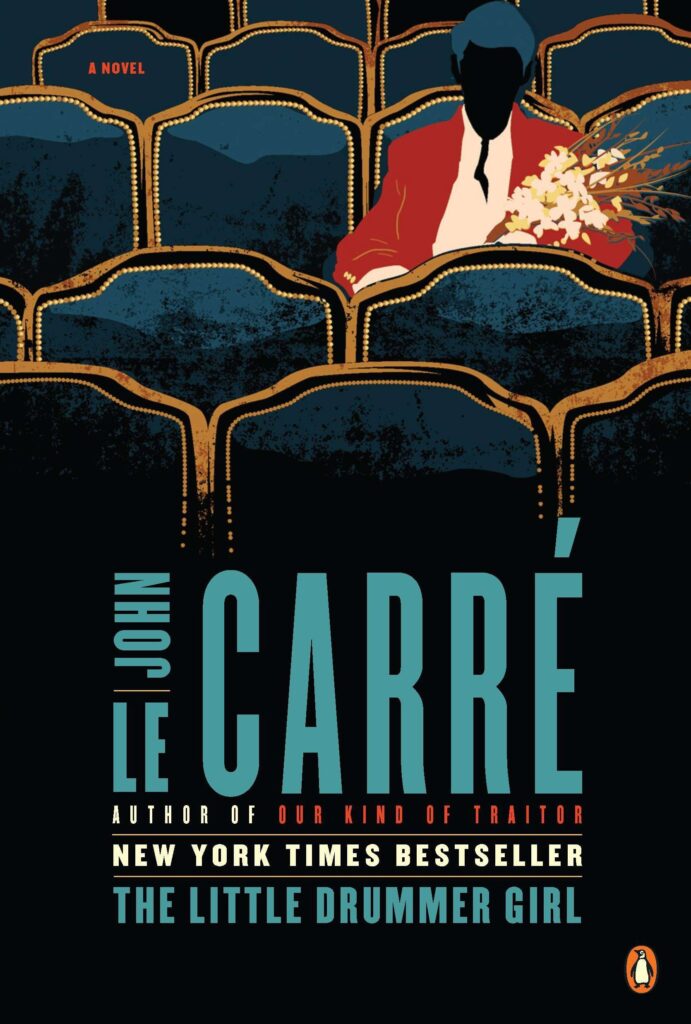

Transmission received from Spybrarian Matthew Kresal: Review of The Little Drummer Girl by John le Carre.

One of the familiar tropes of the spy genre is an intelligence agency recruiting a civilian into an operation. In fact, one might even say it's become a cliche at this point. So perhaps it comes as something of a surprise that widely acknowledged master of the genre John le Carré wrote such a tale himself. The novel in question wasn't one of his tales of Cold War intrigue, however, but explored another conflict all together: the ongoing struggle between Israel and Palestinian terrorists.

The plot of the novel is simple on the surface. Indeed the novel's Wikipedia page sums it up most succinctly in two paragraphs. Following a series of bombings targeting Jews in Europe including one in Bad Godesberg that takes the life of a small boy, a section of Israeli intelligence hatches a plot to track down the bomber responsible. To do so, they will need the bomber's brother but also the help of a Westerner seen to the sympathetic to the cause. The person in question, the title character, in fact, is the twenty-something Charlie, a member of a touring theatre company who finds herself drawn into what her handlers term “the theatre of the real.” The novel follows her recruitment, training, journies across Europe and the Middle East, and the consequences of being thrown into this so-called theatre.

Published in 1983 on the back of the celebrated Quest For Karla trilogy, readers can find certain hallmarks in The Little Drummer Girl as well. There is the ever-present sense of location for example ranging from West Germany in the novel's opening, dingy multi-purpose theatres across the UK, sunny Greece, or Palestinian training camps somewhere in the disputed territory between Arab nations and Israel. It is that “you are there” feeling that comes out in novels like The Honourable Schoolboy and Smiley's People that's present here throughout, making this an eye-opening journey into this world that has the feel of having been experienced at, least in part, first hand by the author himself. (le Carré goes into some depth about the fact in the introduction to later editions of the novel and his more recent memoir.)

Which brings us to the problems the novel has. Issues that it has in common with The Honourable Schoolboy and A Delicate Truth, two of this writer's least favorite le Carré works. Simply put, the novel seems plodding for much of its length. The first two-thirds, in particular, can make for less than appetizing reading as the reader is taken step by step through Charlie's recruitment and the creation of her legend as an agent. To his credit, le Carré handles it better than some writer's and his sequences have a strong sense of verisimilitude to them. That is also their biggest problem as they become repetitive and even dull after a time as details are driven again and again into Charlie's actor's memory.

It's possible that wouldn't be as much of an issue if not for the novel's other problem: it's lack of sympathetic characters. It is hard to latch onto Charlie, the self-absorbed habitually lying twenty-something English actor at the novel's heart, for much of that same time frame. The same can be true of virtually everyone we meet from her cast of fellow actors to the Israeli agents who recruit and run her. It's not because they are outright villains or poorly created characters for the opposite is indeed true. Perhaps the problem is that they are too well drawn, a bit too real and conflicted with shades of gray that become so hard to discern one might need the literary equivalent of a magnifying glass. There is no one to latch onto throughout the lengthy recruitment phase of the novel, making it even more of a slog than it might have been.

And yet the novel redeems itself. The final third of the book as the operation, at last, goes into effect ranks among the best writing I've seen from le Carré. It's a journey that will take Charlie from Europe to the Middle East and back again, one that finally humanizes her and makes her a sympathetic character. One who is suddenly all too aware of the stage she's on, how fragile the proverbial boards are, and the conflicting sides of the opposing forces of this drama. Charlie and the novel race towards the conclusion and with it a growing sense of conflict about her place within it all. Charlie has become a method actor in this theatre of the real, a little too deeply immersed in her role and for which the consequences for her and the reader alike are equally tragic. And unlike A Delicate Truth, this ending as the plot finally kicks into gear never once feels rushed, something which makes the novel all the better and devastating.

On a purely personal level, I have never spent as long reading a le Carré novel as I did this one. I spent five days short of three months reading it. That's twice as long as I spent reading the significantly longer A Perfect Spy nearly a decade ago and longer than I've spent reading far longer novels by Tom Clancy years before that. I felt tempted to give up on it at times, especially in the lengthy first two-thirds. Members of the Spybrary Facebook group convinced me otherwise and, honestly, I'm thankful they did.

The Little Drummer Girl is perhaps not le Carré's best book. It is most certainly not his easiest to read. It is, however, if you can stomach it, a worthy read for being something different from this master of the genre. It's already been adapted once for the screen already and is soon to be seen again as a limited series via the BBC and AMC. That seems appropriate in a way. As le Carré himself says in his introduction, given a few minor changes in detail, it's a story that could as easily happen today as it could have in 1983.

Enjoy chatting about Spy books and movies? Come and join us on the Spybrary Listeners Facebook Group!

a Delicate Truth plodding?