Jump to…

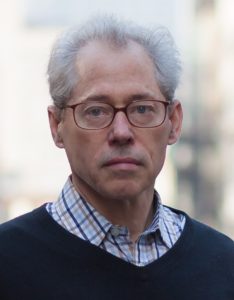

Do we have a treat in store for you spy book fans! Many of you will know Tim Shipman as the Chief Political Commentator at the Sunday Times or maybe you know him as the author of All Out War? But did you know that Tim is also a huge fan of spy books and boasts his own very impressive Spybrary? In this exclusive Spybrary feature Tim is going to share with us his top 125 spy authors ranked!

UPDATE – On August 7th, we hosted our first ever live episode of Spybrary. A panel to discuss Tim's list of the best spy writers. Tim revealed more about his method and criteria for selecting this monster list of spy authors. Joining us were Professor Penny Fielding, author and critic Jeremy Duns, spy blogger Matthew Bradford, and John le Carre book collector Steven Ritterman to run the rule over Tim's pick of the best spy writers. You can watch the discussion below or listen in via your podcast app.

Or listen here

I blush when I think back to the early days of the Spybrary project. I worshipped at the altar of Len Deighton, John le Carre, and Ian Fleming. I had no idea that there was such a wide universe in the spy book genre with so many talented spy authors that I had yet to discover. Buckle up and get that credit card ready as Tim takes us on a journey highlighting and showcasing his top spy authors.

Before we dive in, four items for you to consider.

1 – We are not all going to agree with Tim's top spy authors and that is fine. We hope this feature will help you discover new spy novels or revisit the work of spy authors of yesteryear. Do come and share your views in our friendly Spybrary community. Tim welcomes and encourages constructive debate and discussion.

2– I will update this blog post as often as I can but definitely weekly, sadly that East German desk is rammed at the moment, what with Dicky Cruyer never writing his own reports but it pays for my spy books.

3– Please please if you can buy any of the spy books listed directly from an independent bookstore/shop that would be epic. I am using Amazon links on this page because Spybrary is a global community. Use it for reference, price checking, reviews, etc and try and buy locally or at least independently if you can.

4. We are very lucky that Tim is giving up his time to write this for us. He interviews Prime Ministers and Presidents for a living, so please consider sharing this feature with friends and peers.

Take it away Tim!

With Spybrary Founder Shane Whaley‘s permission, I’m going to commence a new list : a countdown of my top 125 spy authors. This is my third such list hereafter ranking the John le Carre novels and the James Bond films (coming soon.)

This list has been a long while in gestation and brings together everything I know and love about spy fiction.

The idea is to introduce some of you to authors you may not be familiar with and to provoke a discussion about their relative merits.

Spy fiction is a broad church, of course.

You will find here, full-time spy novelists, detective writers who dabble in spy fiction on the side, literary authors who have tried their hands, career intelligence officers, cerebral leading men and women, action man adventure thrillers with a spying element, some classics of the genre and a few one-hit wonders.

The main focus is the Cold War, but it also includes a lot of wartime espionage and a very small flicker of American blockbuster fiction, which my friend David Craggs refers to as “the Kalashnikov kids”.

As you will see, my taste leans heavily towards the more cerebral spies (I’ve never read Brad Thor, Lee Child, or Mark Greaney), but I’m also a fan of excitement, suspense, and tension.

Clever doesn’t have to be boring.

I like great writing, characters you care about, snappy dialogue, and a moody sense of time and space as well as plots that twist and turn, that surprise and shock. (Nearly) everyone here has some of these attributes.

In compiling my top spy author rankings, I have tried to judge people based on a body of work, but those with a few great works stand shoulder to shoulder with people who churned out far more. But, generally, if you published a full series at a high level, you’re going to rank higher than someone who turned their hand to a couple of spy books.

There are authors here (Philip Kerr and Ross Thomas to name two) who perform well but would be much higher for their overall body of work. They deserve a place here, but they are better known for their non-spy work and fall here behind some who devoted their entire canon to espionage.

Are there 125 spy authors worth the trouble?

Randall Masteller’s brilliant site, Spy Guys + Gals, currently lists nearly 2,000 different spy series, from many hundreds of authors.

He currently gives 149 of them a grade of A or better. Of these, not all are pure spy fiction, but his site is a great resource and it has helped me find many great books. I haven’t read nearly as much as Randall, or even the great Mr. Craggs.

The only rule for inclusion here is that I have to have read an author for them to appear, and to get high I must have read a good number of their books. A final note: this is not an attempt to quantify the greatest authors, it is MY list of 125 spy writers I like in the order I like them.

There are many more spy authors I need to read. I will soon add to this the 30 spy authors I most want to read to make up a full list of 150 and to cover some people who may be unjustly excluded. I would hugely value all your opinions about what follows, particularly where you strongly disagree.

I’m going to be updating this post every day and will send it to Spybrary weekly, culminating in the top 10 spy writers. Some entries will be quite short, others will be much more detailed. You might think you can guess a lot of what will follow, but I hope you find some of it, including several top 10 entries, surprising.

But wait there's more…!

The Other 170 must-read spy authors by Tim Shipman.

Let’s just call this project the Top 300 spy writers. As promised, I’ve now augmented the main list of 125 best spy writers I have enjoyed with what follows: more than 170 new spy writers who should be read…

A NOTE ON SOURCES

I've been crediting a lot of people along the way, but several reference works have been invaluable in checking details and jogging my memory about these authors. The two most important are Randall Masteller's brilliant website, Spy Guys & Gals, which is an absolute treasure trove of information.

At the British end, the expert is Michael Ripley, whose book Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang, the boom in British thrillers is absolutely essential for Spybrarians. After that the website Good Reads has a lot of reviews that are worth reading (and a lot that are not), Fantastic Fiction fills in some gaps and Wikipedia does most of the rest.

Without Randall and Mike particularly I would not have come across a lot of the writers here. I'm hugely grateful. I'd also like to give a shoutout to the blog Existential Ennui, which has a lot of brilliant material on spy fiction and collecting first editions, though the guy behind it has spent several years focusing on other genres like science fiction. The other key source, of course, is Spybrary, which includes the greatest group of thriller fans I know. We all owe Shane Whaley a huge debt of gratitude for bringing us together. In terms of reading advice, I'm grateful to Jason King, Matthew Bradford, and Jeff Quest in particular.

Tim would love to hear your thoughts on his top spy author list, either leave a comment here or better still why not join us on the Spybrary Facebook group and read observations on Tim's list written by your fellow spy fans.

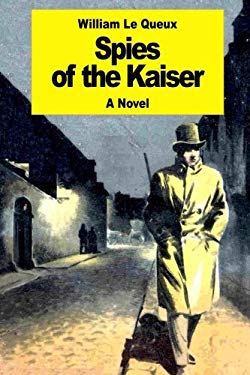

125. WILLIAM LE QUEUX

Active: 1891-1931

Key works: The Invasion of 1910, Spies of the Kaiser

Let’s be frank if this was a list of 1,500 spy writers William Le Queux would probably be 1,500th on the list. By modern standards his propagandist penny dreadfuls from the early part of the 20th century are fairly unreadable, focusing as they do on paranoia about French and German spies under the bed.

But these are arguably the first popular spy novels in England and Le Queux joined forces with newspaper magnate Lord Northcliffe to publish pulp fiction for the credulous masses.

As such they are a fascinating insight into the mindset of the times, particularly in the run-up to the First World War. (Le Queux himself demanded protection by the police from German agents at the start of the war – a demand that seems to have been met with hilarity by the Metropolitan police).

The Invasion of 1910, serialized in the Daily Mail in 1906 sold a million copies in book form and was translated into 27 languages. All spy fans should try a bit of Le Queux.

Spybrary suggested further reading: Le Queux: How One Crazy Spy Novelist Created MI5 and MI6

124. FRANCINE MATHEWS

Active: 1994-

Key works: The Secret Agent, The Cut Out, The Alibi Club

Francine Mathews spent four years as an intelligence analyst at the CIA, including work on the Counterterrorism Center's investigation into the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103, over Lockerbie in 1988.

She has since penned more than 15 books, most of them detective thrillers set in her native Nantucket. But she has also put her intelligence background to good use in a handful of pacy spy thrillers. They skip along and have enough of a ring of authenticity to lift them above the run of the mill.

Further reading: Denver novelist Francine Mathews finds inspiration for thriller in Ian Fleming

123. GÉRARD DE VILLIERS

Active: 1964-2013

Key works: The Madmen of Benghazi, Revenge of the Kremlin

France’s most prolific spy writer penned 200 books about his hero Malko Linge at the rate of four or five a year and sold 120 million copies. Curiously, France’s answer to James Bond is actually an Austrian prince who works for the CIA and the series is known there as the SAS books (equivalent to HRH in English).

The writing is more slapdash than Fleming and they are not for the faint of heart since de Villiers revels in fairly explicit sex scenes every few pages. Nonetheless, there is actually a perverse realism to some of it.

Gerard De Villiers was known to hang out with French intelligence officers and wrote several prophetic books about real life events. Very few of these are available in English, but I’ve tried the Madmen of Benghazi and Chaos in Kabul, the first two translated after his death and there are three others with a Russian theme. They’re salacious fun.

122. CHRISTOPHER WOOD

Active: 1977-79

Key Works: James Bond, the Spy Who Loved Me, James Bond and Moonraker

Wood was a screenwriter responsible for two of Roger Moore’s best-known Bond films, including The Spy Who Loved Me, which for me is one of the all-time greats and Moonraker, arguably one of the worst. He also penned two novelizations of the films and became the first Bond continuation author since Kingsley Amis.

These books are surprisingly decent, particularly the first and have acquired greater kudos in the Bond collector community because most of the hardback first impressions found their way to libraries and are almost impossible to find in good condition. Even a library copy will set you back £200 while a clean non-library version is £500+.

121. JOSEPH FINDER

Active: 1991-

Key works: The Moscow Club

Finder is best known for the Jack Reacher-style series featuring his character Nick Heller and he has also written books featuring industrial espionage, which has a lot of similar themes to the ones we Spybrarians enjoy. However, he’s primarily here because he began authorial life knocking out a couple of decent spy thrillers. The Moscow Club features a KGB coup against Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Extraordinary Powers recounts the discovery of a Soviet mole in the CIA. He’s a highly professional writer, who understands tension.

120. GAYLE LYNDS

Active: 1996-2015

Key works: The Last Spymaster, Masquerade

Known as the Queen of Espionage Fiction (at least in America where she founded the group International Thriller Writers with David Morrell (author of the Rambo books). Gayle Lynds also spent time at a government think tank where she earned a top secret security clearance. Her first book, Masquerade, in 1996 became the first spy bestseller by a woman. Like Mathews, she writes for the pacy airport end of the market, but there is enough insider knowledge to reward die hard spy fans.

119. WILLIAM F. BUCKLEY JR.

Active: 1976-2005

Key works: Saving the Queen, Stained Glass, Who’s On First

Bill Buckley was arguably the most celebrated Conservative political writer in America in the latter half of the 20th century, a serious public intellectual and founder of National Review, a magazine that did much to incubate debate on the right.

He was also the author of 11 rather less serious, but undeniably fun, spy thrillers featuring Blackford Oakes, a charming but rebellious spook. These books, of which I’ve read a couple, are escapist but contain a clear world view where the CIA are the good guys and the KGB are the bad guys.

Buckley, who had little time for the moral ambiguity of Le Carre, was inspired to write the first by reading Frederick Forsyth’s Day of the Jackal. If his mission to entertain was successful the result is perhaps too consciously lightweight to be enduring but they are an amusing diversion.

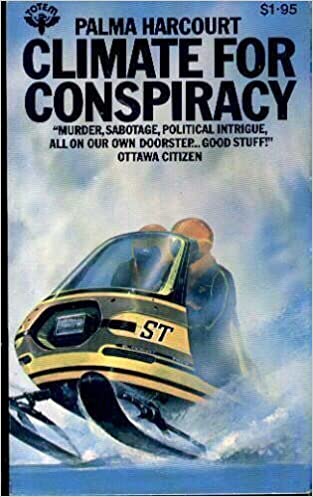

118. PALMA HARCOURT

Active: 1974-96

Key works: Dance for Diplomats, Climate for Conspiracy, Shadows of Doubt

Another female spy writer who has been largely lost to the mists of time. What got me trying her was a cover quote from Desmond Bagley proclaiming: “Palma Harcourt’s novels are splendid”, which is measured enough to be accurate praise, rather than the hyperbole that passes for advertising on many books these days. The paperbacks of her espionage thrillers market her as a new Helen MacInnes.

Harcourt’s books tend to be set in the diplomatic milieu, of which she clearly has personal experience, making them a little different from agency-focused spy fiction.

Low key but rewarding reads.

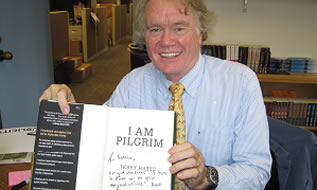

117. TERRY HAYES

Active: 2013-

Key works: I am Pilgrim

Terry Hayes is a man of many parts, but so far the author of only one novel. Hayes is a highly successful screenwriter whose credits include two Mad Max movies, From Hell, Payback and Dead Calm.

When his book, I am Pilgrim, was released in 2013 it was hailed by publishers as “the only thriller you need to read this year”. Perhaps that was because, at 700 pages, it would be the only thriller some people had time to read that year. But that’s a cheap shot.

There are very few thrillers that seem to divide opinion like this one. Some reviewers declare it the best thing they’ve ever read. For me, there are some brilliant set-piece passages that, had he had a stricter editor, could have placed this in the stratosphere, but too much padding and implausibility between them to make the whole hang together very satisfactorily.

A sequel, The Year of the Locust, was planned for release in 2016, but has yet to see the light of day. Wikipedia wryly notes: “Publish dates vary from 2020 to 2045”.

If he nails that one Terry will be moving up, if it’s just as flabby he may be moving out.

116. HENRY S. MAXFIELD

Active: 1958-1960s

Key works: Legacy of a Spy

Henry S Maxfield did a few years on the Berlin desk of the CIA before leaving the agency. In 1958, his first book, Legacy of a Spy, was published and was made into the 1967 movie, The Double Man, starring Yul Brynner and Britt Ekland. I haven’t seen the film.

The book is fairly hard to come by but has a premise that is well explored. As GoodReads puts it: “Montague was a steel-nerved, quietly brilliant counterespionage agent. Carmichael was Comrade Slazov's next assignment for killing. The shadowy Ilse loved a man who called himself Slater. One of the three would probably have to kill Ilse. Neither Slasov nor Ilse suspected that the three were one man.”

Cue a tense and absorbing novel with some interesting tradecraft and multiple swapping of outfits and identities. Maxfield wrote a few other books, but so far as I’m aware only one other spy novel: A Dangerous Man, which I haven’t yet found.

115. ANTHONY TREW

Active: 1963-89

Key works: Two Hours to Darkness, The Zhukov Briefing

Anthony Trew served with the Royal Navy and the South African navy in the Second World War, gaining experience in the Atlantic, the Mediterranean and on the Arctic convoys. He commanded the escort destroyer HMS Walker and won the Distinguished Service Cross. All of which means, as you would expect, that he writes very well about the sea. Unlike a lot of maritime thriller writers, his plots, while not pure espionage, contain a spying element. They also tend to have characters that have a little more depth and drive the plot, rather than bob like flotsam atop it. This is certainly the case in Two Hours to Darkness, written just a year after the Cuban missile crisis, which features the commander of a nuclear submarine coming a tad unhinged. I also enjoyed The Zhukov Briefing, where a Russian sub runs aground in Norway and the world’s intelligence agencies descend to try to steal its secrets.

114. ANDREW GARVE

Active: 1965-71

Key works: The Ascent of D13, The Ashes of Loda, The Late Bill Smith

Andrew Garve was the pseudonym of journalist and crime writer Paul Latimer, who penned more than 40 books, a handful of which were espionage thrillers. His best known and the one that gets him in here was The Ascent of D13, a thrilling mountain climbing thriller, where agents from East and West second on the mountain where a hijacked plane carrying a super weapon has come down. It’s not just gripping, but the denouement is ingenious.

113. Colin Forbes

Active: 1969-2006

Key works: The Heights of Zervos, Double Jeopardy, Avalanche Express, The Stockholm Syndicate

Colin Forbes

A pseudonym of Raymond Harold Sawkins, it is a curiosity that anyone seeking to write thrillers should choose to call themselves “Colin” but we must put that aside. Forbes is one of the most difficult “spy” writers to evaluate. Some of his early stuff is really quite good (The Heights of Zervos stands out as a wartime adventure thriller) and he created a durable spy chief series featuring a British intelligence boss called Tweed (beginning with Double Jeopardy), which ran for years at a time when most people were writing standalone thrillers.

For awhile in the 1980s he was spoken of by some in the same breath as Freddie Forsyth. Forbes’ schtick was that he visited everywhere he wrote about (at a time when cheap air travel was impossible) so his books have what some see as an air of verisimilitude. Critics might say that too often they descend into an arid version of the Baedeker guide. Mid period Forbes is merely formulaic, late period Forbes is to be avoided. Serious people think he kept publishing after he had become senile and things don’t hang together well. Avoid the dreadful Lee Marvin film of Avalanche Express.

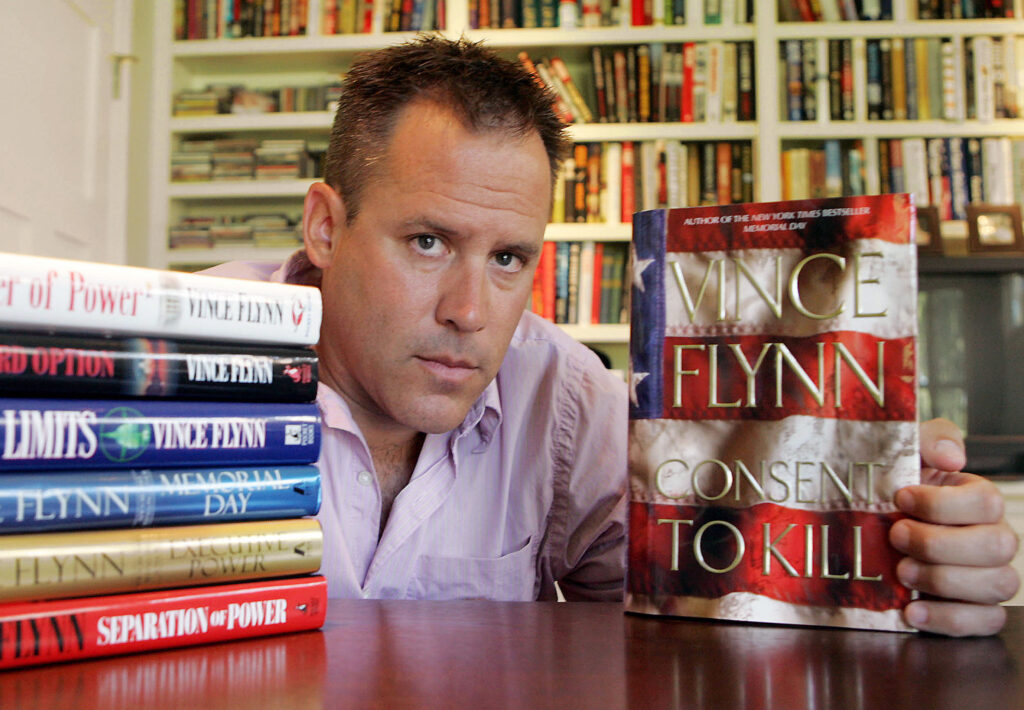

112. VINCE FLYNN

Active: 1999-

Key works: Transfer of Power, American Assassin, Term Limits, Memorial Day

Ok, here’s my one concession to Kalashnikov kiddery. Mitch Rapp is one of the landmark shoot ‘em up spies of the age. I have little to compare him to, since I haven’t tried Jack Reacher, Court Gentry and the others. Randall Masteller, who has read more spy books than anyone else alive says Reacher is the gold standard, but Flynn writes with a fairly gripping exuberance and when I lived stateside he was one of my go-to airport novelists when I needed an amuse bouche for the brain. Flynn’s first, Transfer of Power, is almost absurdly gripping tale of terrorists seizing control of the White House. Go on Craggsy, give it a try…

111. TIM SEBASTIAN

Active: 1988-1997

Key works: The Spy in Question, Spy Shadow

Tim Sebastian was one of the foremost foreign correspondents of his era and his credentials for this sort of thing include being expelled as the BBC’s Moscow correspondent in 1985 accused of spying… He penned a series of moderately successful spy thrillers. None is spectacularly good but they all have a realism and documentary grittiness which you would expect of someone who knows the mean streets of Moscow and Warsaw and crossed paths with people in this world.

110. JAMES NAUGHTIE

Active: 2014-16

Key works: Paris Spring, The Madness of July

Another BBC man, James Naughtie is best known for his two decades presenting Radio 4’s flagship current affairs breakfast show Today, and a series of non fiction books on political subjects. In his dotage he has penned two rather good thrillers.

Where Sebastian is a shoe-leather reporter, Naughtie is an ideas man, a more elegant writer and someone good at conjuring a sense of time and place. The Madness of July features a spy on the hunt for family secrets in 1970s London and Washington. When I met Naughtie at the Borders book festival a few years ago, he asked if I had read his second, Paris Spring (set in the revolutionary fervour of 1968), then frogmarched me to a till and signed the paperback. “This one is better,” he said. He was right.

109. DEREK LAMBERT

Active: 1969-97

Key works: I Said the Spy, The Yermakov Transfer, Red Dove, The Man Who Was Saturday

Derek Lambert was a foreign correspondent for the Daily Express and knocked out very serviceable thrillers throughout the 1970s and 1980s, mostly with Cold War themes and sometimes touching on the Cold War space race. His best known is probably The Yermakov Transfer, which features a plot to kidnap the Soviet premier on the Trans Siberian Express. My favourite is I, Said the Spy, a tale of double-crosses and paranoia set around the mysterious Bilderberg conference of world leaders.

Are you enjoying Tim's spy author rankings? Then why not check out Tim Shipman's favorite John le Carre novels ranked!

108. E. PHILLIPS OPPENHEIM

Active: 1888-1943

Key works: The Great Impersonation, General Besserley’s Puzzle Box, General Besserley’s Second Puzzle Book, The Spy Paramount, Miss Brown of XYO

One of the pioneers of the spy novel from the first golden age of thriller writing, Oppenheim’s career took off in 1898 with the publication of mysterious Mr Sabin, an invasion threat fantasy worthy of Le Queux. However, unlike most Le Queux, some of his later 100-plus novels are actually still very readable and several of his best known works have been reissued in paperback in recent years. These include The Spy Paramount, which features an American sent undercover by a spy chief from fascist Italy, with lovely bold cover art in the 2014 reissue. His best known book is The Great Impersonation (1920), which has a classic doppelgänger plot and doesn’t end up being quite what you expect. I haven’t read them yet but connoisseurs are also fans of Oppenheim’s two volumes of short stories featuring spy chief General Besserley. Miss Brown of the XYO, another spy yarn, was unusual for the time in featuring a female lead.

107. VLADIMIR VOLKOFF

Active: 1979

Key works: The Turn-Around

A French writer of Russian extraction, most of Volkoff’s oeuvre, which features several historical novels about Russia, is not available in English. The one book which is, The Turn-Around, is a very unusual and interesting spy novel. Volkoff is a literary writer and his take on the turning of a double agent is interesting because it explores the inner world of the Russian target and how his discovery of a faith in something other than the communist system helps and hinders the operation. It’s not a thrill a minute but as a character study in the psychology of betrayal it ranks quite highly.

106. SIMON MAWER

Active: 2012-15

Key works: The Girl Who Fell From the Sky, Tightrope

Simon Mawer is a novelist who has tried his hand at espionage. Mawer has 13 books under his belt but the two which interest us here are The Girl Who Fell From the Sky and its direct sequel Tightrope. They feature a very strong female lead Marian Sutro, who is recruited by SOE and parachuted into France as a resistance courier. Her real mission is to contact an old boyfriend in Paris who is a nuclear physicist. Tightrope picks up Marian’s story in the Cold War of the 1950s. These a very well crafted books, where plot is driven by a character

105. BRYAN FORBES

Active: 1986-89

Key works: The Endless Game

Forbes is another of those Renaissance men who obviously love spy fiction and then dabble alongside other career paths. Forbes was a film director, who made The Stepford Wives and Whistle Down the Wind.

He was also the screenwriter for The League of Gentlemen, one of the top heist movies of the 1960s and won a BAFTA for the screenplay of The Angry Silence. So writing thrillers was only the third string to his bow but in the late 80s he penned a few pretty decent spy thrillers (though they’re less well known than his book International Velvet). The Endless Game is a classic Cold War plot with moles and femme fatales and high government politics. It became a fairly lacklustre film, which Forbes also wrote and directed. A Song at Twilight and is a politics-espionage crossover, and Quicksand use the same main character.

Now we're getting serious…

Tim shares the spy writers who will likely not make his top 125 ranking of spy authors

104. DAVID WOLSTENCROFT

Active: 2004-06

Key works: Good News Bad News, Contact Zero

David Wolstencroft is the creator of Spooks, the BBC series about the British Security Service, which was renamed MI5 in America. He also penned two decent spy thrillers, which have good characters and highly cinematic and pacy. The first – Good News, Bad News – has one of those arresting concept openings, where you quickly learn that two guys working in a phot processing booth are both spies targeting each other. It gallops along with endless twists, which even the author admits become too much, but it’s exciting and different from a lot of spy fiction. Contact Zero has another good premise, a bunch of burned young spies, who have seen most of their colleagues killed, seek out the eponymous organisation, which is supposed to help agents who are burned. It’s less breakneck but a more mature book.

Check out the Spybrary Spy Rewind MI5/Spooks Review

103. DOV ALFON

Active: 2019

Key works: A Long Night in Paris

An Israeli journalist, who once edited Haaretz, a respected paper, Dov Alfon took the spy writing world by storm in 2019 with his debut novel, A Long Night in Paris. It’s a multi-perspective thriller that canters along at a good pace and has some interesting top-level political betrayal as well as espionage action. It won the Crime Writers’ Association International Dagger that year and the Marianne award for the top thriller published in France that year. Most importantly, he made Spybrary’s best spy novels of the year, compiled by Craggs/King. He’s now working at Liberation in Paris. I just hope he writes some more.

102. MANDA SCOTT

Active: 2019

Key works: A Treachery of Spies

Another spy breakthrough novel of 2019 was Manda Scott’s A Treachery of Spies, one of the best thrillers I’ve read about the French resistance. It also made the Craggs/King list and was a Sunday Times thriller of the month.

Scott is the author of a series featuring a spy in Roman times and another series about Boudicca, so she knows how to write and how to structure and what you get here is a mature book with strong characters and a dual timeline after a modern murder is committed that resembles the way traitors to the resistance were executed. It’s good on themes of betrayal and memory and how collective history shapes us all. It’s also pretty gripping. If she wrote half a dozen more like this in our genre she’d be climbing 60 or 70 places.

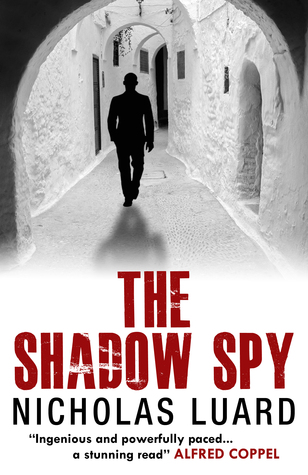

101. NICHOLAS LUARD

Active: 1975-79

Key works: The Dirty Area (aka A Shadow Spy), The Robespierre Serial, The Orion Line, Travelling Horseman

The great joy of this project is that many of the authors turn out to have very interesting back stories. Nicholas Luard co-founded the Establishment club in the London of the Swinging Sixties with the legendary comedian Peter Cook. For a few years this was the beating heart of coolest city on earth, home to groundbreaking comedy and cabaret. As if that were not enough he became one of those who kept Private Eye, Britain’s leading satirical magazine, afloat.

In 1975 he penned The Robespierre Serial, one of those thrillers that was hailed as one of the best of its year, but it’s assassination/manhunt plot owes more than a little to a better-known thriller. Better is The Dirty Area, also known as A Shadow Spy, a title under which it has been republished both in the Colliers Spymasters series, and more recently by Top Notch Thrillers, the imprint Mike Ripley uses to revive great thrillers which have fallen out of print.

The premise is a good one: a disgraced British officer is blackmailed into going to Tangier to impersonate playboy and agent provocateur Ross Callum only to learn that an assassin is targeting Callum. Luard had contacts in the CIA and the word is they bought up copies of several of his books (Robespierre and Travelling Horseman, which takes the reader inside the Black September terror group) for revealing too much about botched field operations.

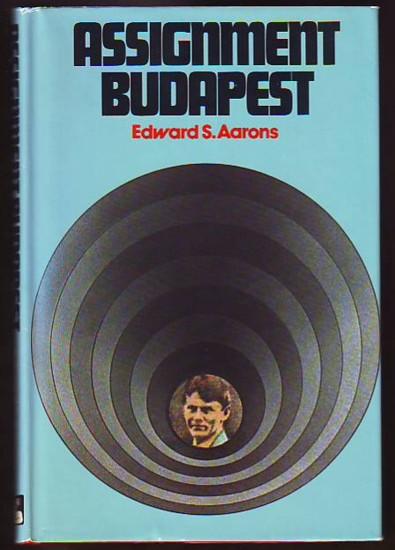

100. EDWARD S. AARONS

Active: 1955-75

Key works: Assignment Tokyo, Assignment Budapest, Assignment to Disaster, Assignment Suicide

Edward S Aarons wrote more than 80 pulp fiction thrillers, 42 of which featured CIA operative Sam Durrell. Every one of them starts with the word Assignment. The first was Assignment to Disaster. Aarons sold 23 million copies and cemented his place as author of one of the great US action paperback series. Durrell is resourceful, his creator the master of the short sharp sentence. The locations are exotic, the action fast and often violent. These aren’t great literature but they are great fun.

99. TREVANIAN

Active: 1972-79

Key works: Shibumi, The Eiger Sanction, The Loo Sanction

Best known to the outside world for the book of The Eiger Sanction, a middling Clint Eastwood movie, Trevanian is the pseudonym of an American film historian named Rodney William Whitaker, who in the 1970s sold more than a million copies of five consecutive books.

That book is rather tenser than the film and its successor the Loo Sanction also has its merits, but they have to be read understanding that Trevanian was trying to both spoof the genre and do it better than many of its authors. Shibumi, which followed in 1979, is regarded as his masterpiece and certainly, it’s a must-read for Spybrarians. On the positive side, the central character, assassin Nicolai Hel, is as compellingly drawn and eccentric as any spy in popular fiction – capable of turning any object into a murder weapon or taking on Japanese experts at the deep mind game Go.

On the downside, the book is all over the place with an absurd digression into a spelunking scene in the Basque country, which lasts for what seems like a geological age. It’s a cult classic and beloved of our man Craggs, but I’m more intrigued to see what Don Winslow did with a prequel novel featuring Hel, Satori, which the Whitaker estate gave its approval to in 2011.

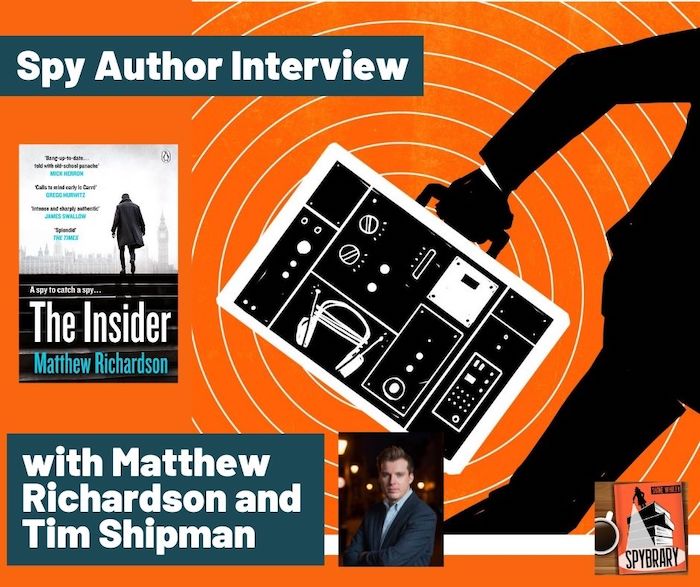

98. MATTHEW RICHARDSON

Active: 2017-

Key works: The Insider, My Name is Nobody

One of the youngest writers in the successful new wave of British spy writing, Matthew Richardson has published two accomplished thrillers and just finished a third, which will hopefully come out next year.

My Name is Nobody came out in 2017 and features his spook Solomon Vine on the hunt for his oldest friend, who has been abducted from the British embassy in Istanbul. It manages to use modern technology and touch on modern themes like terrorism, whilst maintaining an old school feel. Richardson has read a lot in the genre and it shows. It’s not perfect, but Gregg Hurwitz, the author of Orphan X said of it: “I dare you to find a first novel as self-assured, impeccably researched and beautifully rendered.”

The Insider, which I preferred, is Richardson’s modern take on Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. The greatest Russian defector of the age is dead and the suspects include his handlers, who all have top jobs in the security apparatus of the government. Vine is brought in to find the traitor. There’s an even more old school feel to this one. In a recent podcast interview, which you can find on the Spybrary website, Richardson talks up this third, The Scarlet Papers, as his best. He says it’s a much bigger book in scope and length, with multiple time frames building a saga of British intelligence from the war to the modern age.

97. ALEX BERENSON

Active: 2006-18

Key works: The Faithful Spy, the Ghost War

Alex Berenson was a reporter for the New York Times before he began a series of 12 novels featuring John Wells, billed in the opener, The Faithful Spy, as the only American ever to penetrate al Qaeda. That won the Edgar Award for a best first novel.

There followed thrillers which touch on Iran and Russia as well as a return to Afghanistan. But the reason Berenson is here is that he writes about the war on Islamist terror with a subtlety that is not often found elsewhere. I think that period was generally bad for spy thrillers as the enemy was much more difficult to humanise and empathise with than during the Cold War. Many big-name writers tried it and to my mind failed badly. Berenson has done it as well as anyone, frankly.

96. JIMMY SANGSTER

Active: 1967-8

Key works: Private I (aka The Spy Killer), Foreign Exchange

Jimmy Sangster penned nine books, of which two were espionage novels featuring John Smith, a former spook working as a private eye, who is sucked back into the spy business. In Private I Smith does a simple job for his ex-wife and becomes embroiled in a three-way dice between British, Russian, and Chinese intelligence. In Foreign Exchange, he is forced to pretend to defect to Russia to send them duff intelligence, a book which ends with a twist on the last page. These are gritty, hard-boiled books, but also wryly funny.

95. TOM BRADBY

Active: 1998-

Key works: Shadow Dancer, Secret Service, Double Agent, Triple Cross, The Master of Rain

Tom Bradby, now the main anchorman for ITV’s News at 10 is a man of many parts: a journalist who covered politics, the royals, Northern Ireland and the far east, experience he then put to good use in a series of successful thrillers. Shadow Dancer, his first, was praised as one of the best thrillers about the Troubles since Harry’s Game and Bradby adapted it himself for the 2012 film of the same name, which is even better.

The Master of Rain is more detective than espionage but is a brilliant evocation of Shanghai when it was a crossroads for international espionage. More recently he has turned his hand to a trilogy where spying is more central, which begins with the premise that the incoming British prime minister is a Russian mole. Bradby says his next book, Yesterday’s Spy, which features an aging spook whose son has disappeared, which is published in May 2022, is his favourite of all his books.

94. STEPHEN COULTER AKA JAMES MAYO

Active: 1964-77

Key works: The Soyuz Affair, Threshold, Hammerhead, Let Sleeping Girls Lie, Shamelady.

It was perhaps inevitable that Stephen Coulter would create a spy series. He served in naval intelligence during the Second World War, then became a reporter for Reuters and then The Sunday Times. Remind you of anyone? Coulter was, in fact, friends with Ian Fleming and helped him with some background for Casino Royale. Coulter’s character, a transparent Bond clone, was Charles Hood, an art connoisseur and British spy who first appeared in 1964 as the Bond film boom led publishers to seek out anyone with an action man agent. One reviewer described the books as “James Bond with the volume turned up to 11”. These are a decent diversion, but the experts, Mike Ripley among them, think his “outstanding” spy thriller The Soyuz Affair (1977) is his best work and once I’ve read it he might move higher up this list.

93. GEOFFREY OSBORNE

Active: 1968-74

Key works: The Power Bug, Balance of Fear, Checkmate For China, Traitor’s Gate, Death’s No Antidote, A Time for Vengeance.

Osborne’s series of six thrillers about British agents Dingle and Jones were another discovery via Spy Guys & Gals, where Randall gives the series an A minus. These are towards the action end of the espionage spectrum, though their appeal comes from two strong characters, who meet in the first book and a degree of ingenuity in solving problems, which include climbing a Himalayan mountain, seizing a ship from hijackers, plus missions deep behind the lines in Siberia, China and Berlin.

92. GEOFFREY HOUSEHOLD

Active: 1939-82

Key works: Rogue Male

How far up this list can you get with just one book? Certainly this far when the book is a 24 carat classic like Rogue Male, the story of a British sniper on the run after a botched assassination attempt on a unnamed European dictator, whose name presumably rhymes with Mad golf Pitler. It’s one of the great suspense books, though not strictly espionage, Rogue Male came out in 1939. Household followed it up with Rogue Justice, which pitches the sniper into the French resistance, a sequel which came a staggering 43 years later. There are other thrillers – Watcher in the Shadows, which pitches two hunters from intelligence against each other in the 1950s, plus two books featuring a character called Roger Taine – but Household is really only famous for his first outing.

91. ERSKINE CHILDERS

Active: 1903

Key works: The Riddle of the Sands

How far does one book take you? Fair enough. If you haven’t read The Riddle of the Sands, you are missing one of the very first spy fiction classics. It is the story of two young Brits on a sailing trip in the Baltic Sea who uncover a secret German plot to invade England. Like much of William Le Queux’s output it was written as a wake-up call to the British government about the threat from the Kaiser. Unlike Le Queux it is well written and understated. Childers served in the Royal Navy during the First World War, winning a DSC at Gallipoli, and his knowledge of the sea shows. The nautical detail on the shifting sandbanks the heroes have to navigate is highly praised by sailors. The author didn’t long appreciate what he had achieved. Childers became a supporter of Irish Republicanism and smuggled guns into Ireland in his sailing yacht Asgard. He was executed in 1922 by the authorities of the Irish Free State during the civil war.

90. HOLLY WATT

Active: 2019-

Key works: To the Lions, The Dead Line, The Hunt and the Kill.

Are these spy fiction? Not, strictly. But there is much in common between undercover journalists operating with subterfuge on their wits and a secret agent in the field in hostile surroundings. Holly Watt has conjured three diamond sharp thrillers and is fast becoming one of the most acclaimed young writers in Britain.

Her first, To the Lions, won the Crime Writers Association Ian Fleming Steel Dagger, which many successful novelists never win and the follow-up was long-listed. The reason for the success of these books is that Holly has written one of the best female leads in contemporary thrillers.

Casey Benedict is an investigative hack, who specialises in exposing the worst characters. To the Lions featured a hunt with humans as prey, The Dead Line looked at sweat shops and The Hunt and the Kill took on pharma. These books are sweat to the palms tense and the journalistic tradecraft is totally authentic as Holly was for years one of the leading investigative journalists in the land. She spent a few months covering Westminster politics, my stomping ground, and we became pals. I think she was a bit mystified by why I got such a kick out of the personality politics of SW1. She was always pretty secretive about what she was up to outside of the House of Commons and guarded her image closely since she was risking her safety undercover a lot.

The principal pleasure for me in these books is in learning about her skillset and the nerves of steel missions like this take. All I needed was a plausible manner and an ability to handle myself on half a bottle of wine over lunch. If you love the tension of espionage, these books will truly tickle the same adrenaline ducts. And one day, if Casey Benedict is ever hired by MI6, she might give us a traditional spy book.

89. DAVID DOWNING

Active: 2007-

Key works: Zoo Station, Silesian Station, Lehrter Station, Jack of Spies

David Downing has a strong following with his seven book saga on journalist John Russell before, during and after the Second World War. Each of them is named after a station. Fans like the period detail and the story of a man thrust into the mess of great events just trying to survive, along with his son and his girlfriend. Russell finds himself frequently playing off the NKVD against the OSS/CIA and the Gestapo in order to survive. They are literate but have a decent narrative force. I’ve only read two or three of them but Downing has contributed a great deal to the spy world. In 2013 he began a second series, with Jack of Spies, about the early days of British intelligence around the time of the First World War. I’ve never felt Downing quite rises to the heights of the greats, but there is a substantial body of work here which is well worth seeking out.

88. JOHN TRENHAILE

Active: 1981-94

Key works: The Man Called Kyril, A View From the Square, Nocturne for the General, Krysalis, The Mahjong Spies

Trenhaile was a big noise in 1980s spy fiction, though he seems somewhat unjustly forgotten these days. He wrote two trilogies, the Kyril saga and another set in the far east, of which The Mahjong Spies is the first. The three Kyril books are a satisfyingly labyrinthine tale of double and triple agents. Kyril is the codename for a Soviet agent assigned to identify a British mole in the KGB. To do so, he must convince the British that he is a double agent. Meanwhile, a member of MI6 is really a double himself. You get the picture. The series is sufficiently ambiguous that it is never quite clear who is playing who. Trenhaile’s fame derived from a really very good TV adaptation of the books, screened in 1988, which featured a top notch cast of some of the best British character actors of the day: Edward Woodward, Denholm Elliott, Ian Charleson and Joss Ackland. Be warned, the four part series was edited down to a two hour film in the US.

87. DUNCAN KYLE

Active: 1971-93

Key works: A Cage of Ice, A Raft of Swords (aka The Suvarov Adventure), Terror’s Cradle, In Deep (aka Whiteout)

Kyle is one of those authors who would be much higher if this was a list of general thriller writers. He is up there with Maclean, Bagley, Innes and Lyall as an adventure writer of the first rank despite having been largely forgotten. Inevitably, some of his characters find themselves embroiled in espionage, including the protagonist of his first book, A Cage of Ice, who ends up joining a CIA rescue mission in the Soviet-controlled Arctic, Terror’s Cradle where the hero’s girlfriend has become mixed up in the smuggling of microfilm desired by both the KGB and the CIA and Raft of Swords, which features half the world’s spies swarming around a peace conference.

86. FRANCIS BEEDING

Active: 1928-46

Key works: One Sane Man, The Four Armourers, The League of Discontent,

“Francis Beeding” is the pseudonym used by John Leslie Palmer and Hilary St George Saunders, chosen because Palmer always wanted to be called Francis and Saunders had once owned a house in the Sussex village of Beeding.

They worked together at the League of Nations and began to write detective stories in the late 1920s. In 1928 they created the character of intelligence chief Alastair Granby, who starts as an agent and rises to run the secret service. Experts say these have aged better than Dennis Wheatley’s output, though they are a product of their time, warning about the danger to peace in the run up to the war from all sorts of dictators, arms manufacturers and plotters across Europe. Granby works for stability and peace (as the authors doubtless saw themselves doing), trying to stop plots to overthrow governments abroad.

During the war Brendan Bracken, Churchill’s protege, who took over the Ministry of Information, hired Palmer and Sauders to write for the government. One of my favourite first editions is a copy of Eleven Were Brave, which was written in 1940 and deals with fifth columnists in France as the Nazis approached Paris, inscribed to Bracken and signed by both authors and their pseudonym. Well worth a try and if you like them (Randall Masteller gives the series an A+) there are 17 of them. Certainly they should be better known.

85. JACK HIGGINS

Active: 1962-2014

Key works: The Eagle Has Landed, Touch the Devil, A Prayer for the Dying,

Higgins (whose real name was Harry Patterson and who also wrote under the pseudonym James Graham) sold far more books than most people on this list and for a while he was part of a wave of powerhouse British thriller writers including Frederick Forsyth and Ken Follett who took the fight to the Americans with novels pitched somewhere between the classic British actioneers of the 1960s post-Bond boom and the modern US special forces books.

The Eagle Has Landed (1975) is a classic story, well told and a very good film. It has sold more than 50 million copies in 43 languages. One week after it was published Higgins’ accountant phoned him to say it had already made him £1 million.

The Night of the Fox, a twisty tale with an interesting premise, but a pretty poor mini series also had elements of deception and espionage, though they are principally war stories, not spy stories. The same character, Liam Devlin (Donald Sutherland in the film) appears in Touch the Devil and Confessional, both of which feature the Irish nationalist sent into an intelligence battle with the KGB. Sean Dillon, another Irish gun for hire, is the hero of another 20-odd books which primarily features terrorism and assassination plots.

84. ANDREW WILLIAMS

Active: 2009-

Key works: Witchfinder, The Interrogator, The Poison Tide, To Kill a Tsar

Williams was for 20 years a maker of history and current affairs documentaries for the BBC but, after knocking out a couple of well received non-fiction books on the Second World War, he is now making quite a name for himself in the thriller world.

His first historical novel, The Interrogator, is an interesting take on the intelligence battle in the Atlantic war and was shortlisted for both the Ian Fleming Steel Dagger and the Ellis Peters Historical Award. His second, To Kill A Tsar got another Ellis Peters nomination and the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction. I found The Interrogator pretty gripping, the latter disappointingly episodic.

His masterpiece so far, though, is Witchfinder, which brilliantly captures the paranoia inside British intelligence after Kim Philby’s defection and the mad rabbit hole Peter Wright and his ilk descended, turning on their own like Roger Hollis. It’s wonderfully atmospheric, with beautifully drawn characters. It’s a must for all Spybrarians.

83. ADAM DIMENT

Active: 1968-71

Key works: The Dolly Dolly Spy, The Great Spy Race, The Bang Bang Birds, Think Inc

Philip McAlpine is brilliantly described by someone on GoodReads as “the spy Austin Powers wanted to be”. He is the hipster hero of four books by Adam Diment, who for four short years was the coolest dude in spy fiction. Diment’s books combine the wry humour of early Deighton with the sexual cynicism of Bond, with added drugs and rock ‘n’ roll.

The plots are somewhat implausible but the writing, for what it is, is clever. These are time capsule pieces, the perfect encapsulation of swinging London, but the attitudes are of their moment. Many will find the overt racism offputting. McAlpine would have been in trouble from MeToo as well. But if you’re looking for a light-hearted but enjoyable amuse-bouche between meaty books, these are perfect.

David Hemmings was supposed to play McAlpine but the film never got made. To add to their allure, Diment led the life himself, driving an Aston Martin DB5 and dressed like Jason King, before disappearing to become a recluse in the 1970s and, depending on which internet rumour you believe, lived quietly in Kent, blew his mind on drugs, or secretly kept writing.

Further Reading:

Esquire article on Adam Diment – The Extraordinary Case Of The Missing Spy Novelist

82. OWEN MATTHEWS

Active: 2019-

Key works: Black Sun, Red Traitor

I’ve read both of Matthews’ thrillers in the last month. They are of considerable quality, with an interesting, flawed KGB operative hero, who wrestles with a deliciously sinister boss, his libertine wife and his own demons. Both books are highly original riffs on real events.

Black Sun sends Alexander Vasin on a hugely atmospheric mission to the closed city where Russia’s hydrogen bombs were developed and features a physicist modeled on Andrei Sakharov. It’s a murder mystery but leavened with enough internal KGB-GRU intrigue to justify its place in this list.

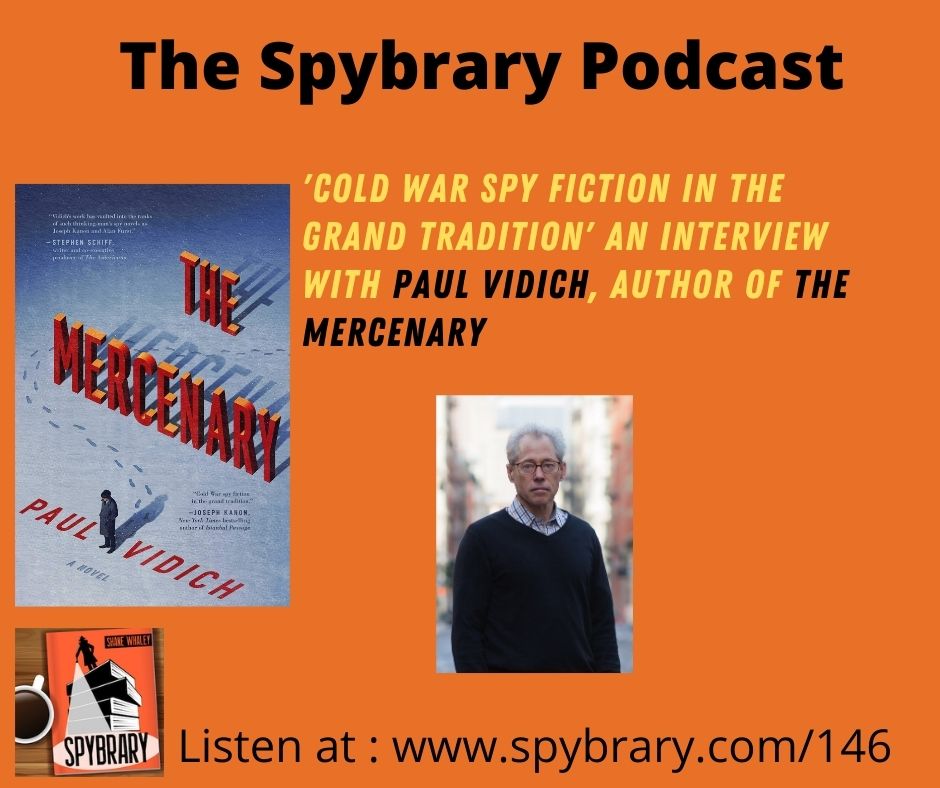

Red Traitor is a gripping foray into the Cuban Missile Crisis, which combines an imaginative reworking of the Penkovsky case and a chilling insight into real-life events on a Russian submarine armed with a nuclear torpedo that was sent to challenge the American blockade with orders to fire. The writing is assured and reminiscent of other historic espionage authors like Paul Vidich and Joseph Kanon. Matthews is half Russian, speaks the language like a native, and was Moscow bureau chief for Newsweek so his drab Russian streets are pitch-perfect. If he keeps at it Matthews has the potential to trouble the top 40 of this list. If that is not enough he is also the author of the definitive English language work on Richard Sorge, Stalin’s Second World War master spy.

81. KINGSLEY AMIS

Active: 1965-68

Key works: Colonel Sun, The James Bond Dossier, Man With the Golden Gun, The Book of Bond

Amis is one of the greatest writers on this list though clearly not one of the greatest spy writers. But he has several claims to inclusion. As an admirer of Ian Fleming, he was probably the first serious figure to take Bond seriously. Amis wrote the James Bond Dossier under his own name and The Book of Bond, or, Every Man His Own 007, a tongue-in-cheek how-to manual about being a sophisticated spy, under the pseudonym “Lt Col. William (‘Bill') Tanner”, who was M's Chief of Staff in many of Fleming's novels.

When Fleming died just as he was finishing The Man With the Golden Gun, it is said that Amis helped to give it a pre-publication polish. This culminated in 1968 when Amis, under the pseudonym “Robert Markham” published Colonel Sun, the first – and for my money, the very best – Bond continuation novel. It’s got a nasty villain, a sexy girl, and a hero who is at the crueler darker end of Fleming’s spectrum. Where others have left their own imprint on Bond, Amis was the most successful at emulating Fleming’s Bond, indeed I would rank it ahead of pushing half of Fleming’s books.

80. Robert Wilson

Active: 1995-2015

Key works: The Company of Strangers, A Small Death in Lisbon

Wilson is a very talented crime novelist. His Bruce Medway series, set in Africa, is reminiscent of Gavin Lyall. His Javier Falcon detective series, set in Seville, has won numerous awards and became a TV series. But he’s here because of two very accomplished, split time historical thrillers. A Small Death in Lisbon won the CWA gold dagger in 1999. It’s a murder mystery, with the timeline switching between Lisbon in 1941, when the city was awash with spies and the SS were in town trying to buy up vital supplies of Tungsten, and Lisbon in 1999 where a murder is linked to old events as the country emerges from the Salazar dictatorship.

Even better, and definitely, a spy novel (one of my favourites to boot) is The Company of Strangers, which pitches a Portuguese woman into the maelstrom of wartime spying, alongside a Nazi double agent, and then follows her into the Cold War. It’s really good and ought to be much better known.

79. Desmond Cory

Active: 1951-71

Key works: Undertow, Hammerhead aka Shockwave, Feramontov, Timelock, Sunburst

Cory was the pen name of the prolific Shaun Lloyd McCarthy, who wrote 45 novels and gave the world Johnny Fedora, a superspy with a license to kill who pre-dated James Bond by two years. One critic described him as “a much more violent, sexy, and lucky agent than James Bond”. The first three all involve Fedora thwarting neo-Nazi movements and there is a sense among the critics that early Fedora has not aged well. However, Cory’s final five books, which form a spy symphony called the Feramontov Quintet, are of higher quality and that’s where I’ve focused my reading energies. Feramontov, a stunted Russian, is a worthy adversary and the books are more stylistically close to the intelligent thrillers Spybrarians enjoy than the brisk adventures of the early years.

78. James Grady

Active: 1974-2015

Key works: Six Days of the Condor

Grady has written 15 novels, but I must confess I’ve only read one of them: Six Days of the Condor. But it’s a belter and gets him this high on its own. It tells the suspenseful story of a minor CIA operative who goes out one lunchtime and returns to find his workmates slaughtered. When he tries to seek help from an emergency number there is an attempt on his life. It’s a real nerve shredder.

The book became a film, Three Days of the Condor, starring Robert Redford, which is one of the cornerstones of 1970s post-Watergate paranoid thrillers. Two sequels followed, Shadow of the Condor (1976) and Last Days of the Condor (2015) but I haven’t read either of them yet. If you’ve only watched the film, give the book a go, it’s rightly a classic.

77. Ian McEwan

Active: 1990-2012

Key works: Sweet Tooth, The Innocent

Another literary novelist who has tried his hand at espionage. Unlike Sebastian Faulks, an author I usually like, but whose attempt at a Bond novel reads like a literary novelist who thinks writing a thriller is easy and somewhat beneath him, McEwan has twice come up with a winner, perhaps because he treated the subject matter like any other subject for literary examination.

The Innocent is a twisty gripper of a book, which embroils a naive telecoms worker in the 1950s tunnel the allies built under the Russian sector of Berlin to tap their communications. He falls for a German woman and his two worlds collide. Sweet Tooth, which came two decades later, pitches a female lead recruited by MI5 in 1972 to penetrate the circle of a rising young writer as part of the intelligence effort to shape the cultural conversation. Then she falls for him. Again, it’s high-quality stuff. If he’d written four like this he’d be way higher.

76. Anthony Horowitz

Active: 2000-

Key works: Trigger Mortis, Forever and a Day, Stormbreaker

Like Amis, Horowitz is here primarily because he is the keeper of the Fleming flame. His two, soon to be three, Bond novels are, for my money, the best and certainly the most faithful homages/additions to the Fleming canon since Colonel Sun. He gets extra points for inserting his works into the existing timeline. There’s no Daniel Craig’s separate cinematic universe here.

Horowitz has two other major strings to his bow. He created the TV drama Foyle’s War which, after Morse had finished, was the best detective drama on British television and included a heap load of espionage plots as well. And Horowitz is also a talented writer for children and his Alex Rider series, about a boy recruited by MI6, runs to 12 books in 20 years. I haven’t read them yet but look forward to doing so when my children are old enough.

75. William Boyd

Active: 2006-

Key works: Restless, Solo, Spy City, Waiting For Sunrise

Like McEwan, Boyd is a “proper” novelist, unlike McEwan he has begun to do a little more than dabble in espionage fiction, finding in it some of the human drama, romance and betrayal that is the stock of literary writers, but perhaps too some pretty decent book sales.

This process began with Restless in 2006 and continued with Waiting for Sunrise. These books impressed the Fleming estate enough that he was commissioned to write Solo, which came out in 2013, sending Bond into a fictionalized version of the 1960s war in Biafra. Some love it, some hate it.

Boyd is also a talented screenwriter, penning the script to the film of Restless and he created the 2020 espionage TV series Spy City, which tells of a molehunt in the British embassy in Berlin in 1961 just as the Berlin wall was about to go up. Let’s hope he has another crack at an espionage thriller since he seems to like and respect our genre.

74. Martin Cruz Smith

Active: 1981-2019

Key works: Gorky Park, Polar Star, Wolves Eat Dogs, Stallion Gate

Another author who is hard to rank, since he is essentially a crime writer, but his main character, Arkady Renko, one of the greatest and best drawn in modern detective fiction is a Russian, who has more than a few run-ins with the KGB and whose work crosses genres.

If I were ranking him as a crime series he would be much higher, but this seems about right when compared to the specialist spy writers who follow. Gorky Park is a classic, which has the vibes of an espionage book though the resolution is not spy related. Polar Star, where Renko is exiled to an Arctic factory ship is even more thrilling. Cruz Smith wrote some stand alones, which have more explicit espionage links, including Stallion Gate, set in the run up to the Los Alamos atom bomb test, but it is not a patch on Joseph Kanon’s Los Alamos.

73. Victor Canning

Active: 1934-85

Key works: The Rainbird Pattern, Firecrest, Birdcage, The Doomsday Carrier

Canning was a ludicrously prolific crime writer, some of whose best work is in the spy genre. In the 1960s he wrote a series of books about Rex Carver, a private investigator who does jobs on the side for the secret service. But Canning’s real purple patch began in 1971 with Firecrest, the first of eight books about Birdcage, a sinister subsection of the British intelligence community. There are a few recurring characters but the agency is the one looming presence, the plots usually about hunting down people going rogue or information coming out (or in one case a plague-carrying chimp).

Critics say his best is the Rainbird Pattern, which I enjoyed, and which won the CWA silver dagger (it was runner up to Ambler’s The Levanter). That book became Family Plot, Alfred Hitchcock’s last film. These are not traditional linear spy thrillers but Canning was an experienced craftsman and they are worth seeking out.

72. Evelyn Anthony

Active: 1953-2005

Key works: The Defector, The Avenue of the Dead, Albatross, The Company of Saints

It is said that Evelyn Ward-Thomas took the pen name Anthony because she wanted to sound more masculine in order to get published, but her virtue actually is that she wrote credible female leads before that was popular in spy fiction. Her early output veered towards romance, with espionage links and she never quite lost that combination of romance and spying (The Tamarind Seed), But, like Helen MacInnes, she wrote effective wartime thrillers laced with spying (The Occupying Power, The Rendezvous).

The place to start, though, is her rather good four-part series about Davina Graham, a female spy sent to interrogate a Russian defector who then falls for him in The Defector, before the series escalates into classic mole hunt territory (The Avenue of the Dead, Albatross) before culminating in a terrorist plot with The Company of Saints.

71. Kenneth Benton

Active: 1969-75

Key works: A Spy in Chancery, Sole Agent, Craig and the Jaguar

Benton was recruited by MI6 in the 1930s and spent the war in Spain, where he was in charge of the counter-espionage unit tracking German spies. After the war, he stayed in Madrid under Kim Philby, an association that ended his career as a covert operative when Philby defected, though he stayed with SIS for some years afterward. Benton penned an enjoyable series about Peter Craig, a police liaison spook skilled in counter terrorism.

The first book, The 24th level, is not a spy book at all, dealing with Craig crossing swords with a diamond syndicate in a mine in South America. But the next two, Sole Agent and particularly A Spy in Chancery, which deals with a mole hunt in the British embassy in Rome, are core Spybrary. Further adventures followed, involving the kidnapping of the niece of the head of MI6 in Peru, Craig’s own capture by Tunisian revolutionaries, and a Saudi Arabian murder mystery. Another effort featuring the defection of a scientist and KGB assassins was published posthumously as an e-book in 2012 (Vengeance in Venice). Craig is an understated but impressive hero and Benton’s experience gives the books an authentic ring.

70. John R. Maxim

Active: 1989-2003

Key works: The Bannerman Solution, The Bannerman Effect, Bannerman's Law, Bannerman's Promise, Bannerman's Ghosts

Maxim is someone I discovered through Spy Guys and Gals, where Randall Masteller gives his series about Paul Bannerman, who runs a group of freelance secret agents, an A++ grade. There are five Bannerman books and four more spun off about other characters in his group, notably assassin Elizabeth Stride.

The first book starts with a great premise, that a bunch of retired spies, killers, and pavement artists all live together in a small town in America, quietly dealing with the local bad guys in their own way. Then the CIA’s head of operations decides to do something about it, which provokes battles of wits, wills, and guns.

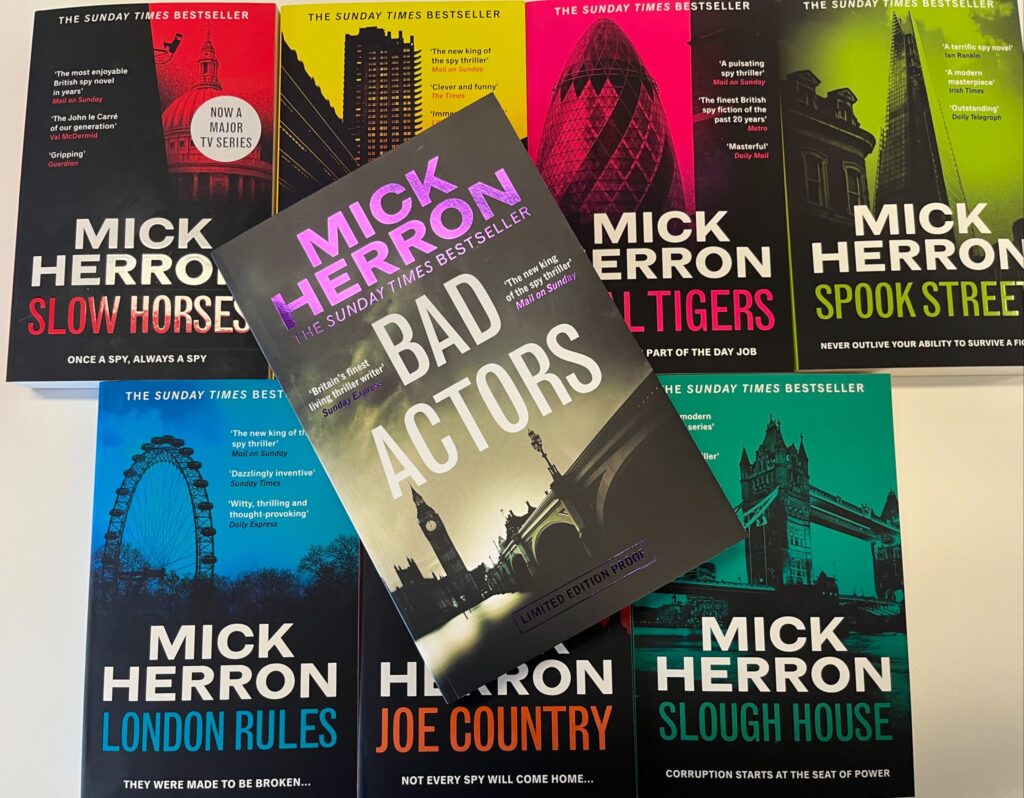

Bannerman’s gang of misfits is hugely resourceful and the man himself is gifted with a great tactical brain that devises twisty and amusing ways to get the better of those the group runs up against. The best way to describe them really is that they are the best eccentric ensemble cast in spy fiction before Mick Herron created the Slow Horses. If I’d read more than a couple, I might well push him quite a bit higher on this list.

70. John R. Maxim

Active: 1989-2003

Key works: The Bannerman Solution, The Bannerman Effect, Bannerman's Law, Bannerman's Promise, Bannerman's Ghosts

Maxim is someone I discovered through Spy Guys and Gals, where Randall Masteller gives his series about Paul Bannerman, who runs a group of freelance secret agents, an A++ grade. There are five Bannerman books and four more spun off about other characters in his group, notably assassin Elizabeth Stride.

The first book starts with a great premise, that a bunch of retired spies, killers, and pavement artists all live together in a small town in America, quietly dealing with the local bad guys in their own way. Then the CIA’s head of operations decides to do something about it, which provokes battles of wits, wills, and guns. Bannerman’s gang of misfits is hugely resourceful and the man himself is gifted with a great tactical brain that devises twisty and amusing ways to get the better of those the group runs up against. The best way to describe them really is that they are the best eccentric ensemble cast in spy fiction before Mick Herron created the Slow Horses. If I’d read more than a couple, I might well push him quite a bit higher on this list.Right, people, the list is back…by popular demand

69. Nelson De Mille

Active: 1974-

Key works: The Charm School, The Lion’s Game

There are not many blockbuster, global spy/action US authors on this list and I want to fit in one more before the obvious big two. Nelson De Mille is not an espionage specialist but he has a few notable books which touch on our genre.

The Lions Game is overlong but a warning about the vulnerability of America to Arab terrorism before 9/11 ever happened and it is spooky to re-read now. The same lead character, the wisecracking John Corey, is also in Plum Island and Night Fall, which are nothing to do with spying but among his highest rated novels.

My two favourites are stand alones, though. By the Rivers of Babylon, where a bunch of Israelis who survive a plane crash, stage a Rorke’s Drift-like defence against a bunch of Palestinian commandos, is very exciting and rather moving. But the reason the author is here is The Charm School (1988), which is a genuinely very high quality spy yarn, which spins a thriller around the notion of a Russian facility that trains KGB operatives to think and behave like Americans to infiltrate the US. Anyone who has watched the TV series The Americans will be familiar with the idea, but this was original when written and is still highly recommended.

68. David McCloskey

Active: 2021-

Key works: Damascus Station

I’ve thought long and hard about whether it is right to place someone this high on the basis of one book, and a book I’ve only just read at that, where the passage of time has not tested how enduring the work is when memories fade. But Damascus Station, the debut of McCloskey, a former CIA man, is the best spy thriller I’ve read in the last year and as a modern debut only perhaps Red Sparrow gripped me in quite the same way.

This is a book that illuminates a complicated conflict in a humane way. It is riddled with authentic tradecraft and features a well-drawn female double agent, who is both intriguing and sexy as hell. Best of all, the really bad villains are vile while many of the others come with their own shades of grey, which illuminate a regime which traps as many of its members as its opponents in a cycle of miserable depravity.

It would be understandable if McCloskey fails to touch these heights again, and he may drift downwards in future, but if he nails a second of this quality he will be jumping considerably higher. Call this a holding slot, but the praise the book has been getting is justified and I can’t wait to read what he comes up with next. I’m putting him here because he represents something of a tier break. I’m excited about what follows because from here on in we really are entering the cream of the crop.

67. Yulian Semyonov

Active: 1966-90

Key works: TASS is Authorised to AnnounceA fair assessment of Semyonov, arguably Russia’s greatest spy/detective writer, is necessarily constrained by the few books of his which have been translated into English.

Best known, of course, is Seventeen Moments of Spring (1969), which features a Soviet agent (Stierlitz, an amalgam of real life agents) impersonating a Nazi inside Hitler’s inner circle at the end of the Second World War. The TV series (1973) is among the most beloved ever screened in Russia, an archetype of the underside of the Great Patriotic War – and it has huge admirers in the Spybrary community, particularly Clarissa Aykroyd.

There were 12 books in the series. The only other one of his I’ve read is a stand alone called TASS is Authorised to Announce (1977), the plot of which concerns the hunt for a CIA spy in Moscow in the 1970s. It is an interesting inversion of the usual memes of wicked Russians and virtuous Westerners. Some of it is a little crude, and i would argue less well-informed about Western society than Anglo-American writers are about the Russian world, but all Spybrarians should try a book like this to understand how “the other side” sees us.

66. Robert Ludlum

Active: 1971-2006

Key works: The Bourne Identity/Supremacy/Ultimatum

This ranking will annoy almost everyone, but particularly my friends Matthew Bradford, who would put the inventor of the globetrotting action/espionage thriller much higher, and Jason King, who believes Ludlum’s doorstoppers are best deployed as alternatives to firewood.

To me, Ludlum is a nice idea, the founder of an entire genre of sprawling seventies epics, but all too often the reality is cardboard characters, expository dialogue, repetitive language and forests of words that could be trimmed. I must admit I haven’t read a lot of what are regarded as his better works (Matthew recommends The Chancellor Manuscript and The Road to Gandolfo, which shows that Ludlum was capable of satirising himself, while The Matarese Circle seems well regarded too).

All that said, The Bourne Identity is a stone cold classic, with one of the great opening premises (man wakes up with amnesia and gradually begins to realise he is a trained killer). Some think the Bourne Supremacy even better. The films are also superior, for the most part, than their Bond contemporaries. Love him, hate him, you need an opinion on him. Try him.

65. Owen John

Active: 1966-76

Key works: 30 Days Hath September, A Beam of Black Light, Dead on Time, The Shadow in the Sea

John (Real name Leonard Owen-John) was a Welsh thriller writer who penned seven quality thrillers about Haggai Godin, a Russian-born spy for MI6, who is a mysterious tactical mastermind. Wikipedia describes him as both “hard boiled” and a “bon vivant”, which is right.

In these books, again unfairly forgotten (except by Randall Masteller who put me on to them) he joins forces with CIA man Colonel Charles Mason. John writes masterful and bloody action sequences and knows how to crank up the tension but these books are much more than that. The Goddin-Mason double act is excellent and there is a great deal of psychological tension.

The first book, 30 Days Hath September, features a chilling depiction of a captured American scientist going mad under torture by his Chinese captors before Goddin hoves into view. Quality tales of the old school which surprise pleasantly with their depth and characterisation.

64. Andrew York

Active: 1966-75

Key works: The Eliminator, The Deviator

York was one of many pseudonyms of the highly prolific Christopher Nicole, one of those thriller writers who ground out book after book (around 200 in total) every year in the heyday of British thriller writing but has been unjustly forgotten by many.

Under his own name, Nicole wrote four good wartime thrillers set in the Balkans (Partisan is the first) and four more on SOE and the French resistance, which veer more into our terrain (try Resistance). There are another nine books in the Angel series, which feature a Nazi sniper who is a double agent for the British (start with Angel From Hell).

As Andrew York he wrote four books about Tallant, the police commissioner from a Caribbean island, which are fun. But Nicole/York’s finest hour is the Jonas Wilde series, which features the titular assassin of the British government.

Their titles are descriptively muscular: The Eliminator, The Dominator, The Predator etc. For me, Wilde is the high point of the post-Bond solo spy-action hero, Bond-alternative genre. Wilde is more sardonic than Bond, the women are often better drawn and feistier, the locales exotic, the double-crosses plentiful. After the first book, my favourite (and the most Spybrary-friendly) is The Deviator, where Jonas crosses sniper rifles with the KGB. These are serious fun and really well crafted by an author who clearly understood the art of thriller writing.

63. David Brierley

Active: 1979-96

Key works: Big Bear Little Bear, Cold War, Czechmate, Blood Group O, One Lives One Dies, On Leaving a Prague Window, Shooting Star

Brierley created Cody, one of the very best female leads in spy fiction. She is a CIA trained agent who has gone freelance, who we first meet in Cold War, a 1979 novel set in the midst of a French election, which involves assassination, betrayal, and real tension (It scores 4.14 on GoodReads, which is much higher than a lot of books I love).

Cody is resourceful and Brierley was hailed on publication as “a new name joins the world’s greatest spy fiction writers”. Best of all his books are not long and written with a spare and unflashy style that nonetheless has real novelistic flair.

This is espionage for grown-ups. Blood Group O, Skorpion’s Death and Snowline followed. Between those Cody books, Brierley also became renowned for spy thrillers set in Eastern Europe, such as Czechmate.

His best book, though, is Big Bear Little Bear set in 1948 Berlin, before the airlift, where the sole survivor of a blown network works to expose a traitor in British intelligence. My paper, The Sunday Times, reviewed it thus: “ Has the rancid strength of a distillation of the best of Le Carré and Deighton: an authentic winner.” That this praise is only slightly excessive tells you what you need to know.

62. Warren Tute

Active: 1969-77

Key works: A Matter of Diplomacy, The Powder Train, The Tarnham Connection, The Resident, Next Saturday in Milan, The Cairo Sleeper

Tute served in the Royal Navy during the war and made a name for himself penning well-regarded non-fiction about aspects of the conflict afterward. His entry here comes from a six-part spy thriller cycle he penned in the 1970s, known as the Tarnham spy thrillers, since they revolve in part around Elissa Tarnham, the wife of a British defector to the Soviets.

The first book, A Matter of Diplomacy covers a visit she makes to Greece, where the intelligence agencies don’t know if she is about to defect too. The other five volumes build on the story but focus on George Mado, a hard fighting, hard drinking former MI6 man who is called into action to cross paths with moles, defectors, the mafia and the KGB. These are unflashy but extremely well put together.

They are mysteries and puzzles, with well drawn characters, rather than shoot-em-ups, weighing in at around 200 pages each, how books used to be.

61. William Haggard

Active: 1958-90

Key works: The Powder Train, The Power House, The Conspirators, The Hardliners, A Cool Day For Killing, Visa to Limbo, The Powder Barrel

Richard Henry Michael Clayton wrote using his mother’s maiden name, which also happened to be the name of his fifth cousin, H. Rider Haggard, he of King Solomon’s Mines fame. Like Tute, his stock in trade is the slow burn, serious, political espionage thriller. In three decades, Haggard turned out 25 books featuring his intelligence chief Charles Russell. A lot of the action here is in Whitehall, an environment Haggard knew well as a longtime civil servant, who appears to have spent at least part of his career in the secret world.

Existential Ennui informs us: “Haggard's own view of his books, which he shared in a letter to Donald McCormick for McCormick's 1977 survey Who's Who in Spy Fiction, was that they were ‘basically political novels with more action than in the straight novel’.

As the Independent put it in his obituary: “His grasp of plot, pace, suspense and set-piece action was, especially in his earlier days, pretty nearly without flaw. He was very good indeed at the labyrinthine, the plot that twists, turns, coils and convolutes, then doubles back upon itself and eventually vanishes up its own jumping-off point.” If the prospect of a Whitehall procedural sounds stuffy, that’s not really the vibe of this series. While Russell (like Haggard) is a bit of a political reactionary, several of the plots involve new scientific techniques and weapons (The first two involve a new form of nuclear energy and negative gravity) with Britain frequently caught in the rivalry between the Russians and the Americans.

Other books cover industrial espionage, defecting scientists, coups in the Middle East, hijackings, dodgy banks, the drug trade, and numerous plots involving politicians up to no good. These are period pieces but they are well done.

60. Anthony Hyde

Active: 1985-96

Key works: The Red Fox, Formosa Straits, China Lake

Anthony Hyde’s first novel, The Red Fox, is quite simply one of the best espionage/mystery thrillers I’ve ever read. It begins with the hero, journalist Robert Thorne, contemplating why his father committed suicide, before his ex gets in touch to say her father is missing. Thorne pursues the mystery and the missing man across time and continents, following clues that hark back to secrets of the Cold War, culminating in a denouement in the frozen wastes of the USSR. The first person narrative is beautifully judged, capturing Thorne’s articulate cynicism with regular revelations which drive the story forward. The Red Fox (1985) came out at the same time as The Little Drummer Girl and The Bourne Supremacy. It’s better than both of them. Hyde was swamped with critical praise.

The pressure of producing a follow up, that tricky second album, obviously told because it took seven years before he produced China Lake, which is not a patch on his first. Formosa Straits, four years later, was better but Hyde is essentially a one hit wonder. His brother Christopher Hyde also wrote a series of solid if unspectacular historical thrillers such as The Gathering of Saints and The House of Special Purpose.

59. David Quammen

Active: 1983-87

Key works: The Soul of Viktor Tronko, The Zolta Configuration

Quammen is better known as a writer on science and nature, where he has published more than a dozen books. However, he wrote one stylish and intelligent masterpiece that I would happily rank among my ten favourite spy thrillers, and just one other thriller (The Zolta Configuration) that doesn’t belong on the same shelf. In the same way that Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy is Le Carre’s response to Philby, Quammen’s The Soul of Viktor Tronko is the supreme response by an American author to one of the greatest mysteries in American intelligence history: the contradictory defections of Anatoly Golitsyn and Yuri Nosenko in the 1960s.